Introduction

Logical fallacies are common errors in reasoning that can undermine the validity and effectiveness of arguments. In discourse and debate, being able to identify and avoid fallacies is essential for constructing sound and persuasive arguments. A thorough understanding of logical fallacies not only helps individuals strengthen their own arguments but also enables them to critically evaluate the arguments of others. In this comprehensive exploration, we will explore into various types of logical fallacies, providing detailed explanations and illustrative examples.

Types

1. Ad Hominem:

Ad Hominem, Latin for “to the person,” is a fallacy in which an argument is attacked by targeting the character, motive, or other attribute of the person making the argument, rather than addressing the substance of the argument itself. This fallacy often manifests in the form of personal insults or attacks. For example:

Person A: “I believe we should implement stricter regulations on environmental pollution.”

Person B: “You’re just a tree-hugger who doesn’t understand economics. Why should anyone listen to you?”

In this example, Person B disregards Person A’s argument by attacking their character as a “tree-hugger” instead of engaging with the merits of the argument for stricter environmental regulations.

2. Straw Man:

The Straw Man fallacy occurs when someone misrepresents or exaggerates an opponent’s argument to make it easier to attack or refute. Instead of addressing the actual argument presented, the attacker constructs a distorted or weakened version of it. Here’s an example:

Person A: “We should invest more in public education to improve student outcomes.”

Person B: “Person A wants to throw unlimited taxpayer money at failing schools without any accountability. That’s irresponsible and wasteful.”

In this scenario, Person B misrepresents Person A’s argument by exaggerating it as wanting to throw “unlimited taxpayer money” without any accountability. It is a distorted version of the original argument for increased investment in education.

3. Appeal to Authority:

An Appeal to Authority fallacy occurs when the opinion of an authority figure is used as evidence to support a claim. In this case authority may not be an expert in the relevant field or if the claim may be outside the authority’s area of expertise. Relying solely on authority without considering the substance of the argument can lead to faulty reasoning. For instance:

Person A: “We should follow this diet plan because it’s endorsed by a famous celebrity.”

Person B: “Just because a celebrity endorses the diet plan doesn’t mean it’s effective or safe. We need to consider scientific evidence and expert opinions.”

In this example, Person A appeals to the authority of a celebrity without providing scientific evidence or expert opinions to support the effectiveness or safety of the diet plan.

4. False Cause:

The False Cause fallacy, also known as Post Hoc Ergo Propter Hoc (Latin for “after this, therefore because of this”), occurs when one event is assumed to have caused another simply because it occurred before it. Correlation does not imply causation, and this fallacy overlooks other possible explanations for the observed relationship between events. An example:

Person A: “Ever since we started using the new software, our productivity has increased. Therefore, the new software must be the reason for the improvement.”

Person B: “There could be other factors contributing to the increase in productivity. We can’t conclude that the new software is the sole cause without further evidence.”

In this scenario, Person A mistakenly attributes the increase in productivity solely to the introduction of the new software. Person A does not consider other potential factors that may have contributed to the improvement.

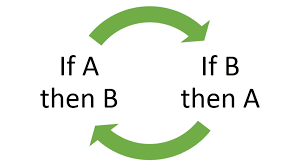

5. Circular Reasoning:

Circular Reasoning, also known as begging the question, occurs when the conclusion of an argument is essentially the same as one of its premises, resulting in a circular, self-referential argument. Instead of providing independent support for the conclusion, circular reasoning assumes what it seeks to prove. Here’s an example:

Person A: “The Bible is the word of God because God wrote it, and we know this because the Bible says so.”

Person B: “But how do we know that the Bible is the word of God?”

Person A: “Because it says so in the Bible.”

In this circular argument, Person A uses the Bible to justify its own authority. Person A is creating a circular reasoning loop that fails to provide independent evidence for the claim.

6. Appeal to Emotion:

Appeal to Emotion is a fallacy in which emotions, such as fear, pity, or joy, are manipulated to win an argument without providing valid evidence or reasoning. By appealing to emotions rather than logic, this fallacy attempts to sway the audience’s opinion based on feelings rather than facts. For example:

Advertisement: “Buy this product now and feel confident and attractive!”

This advertisement appeals to the audience’s desire for confidence and attractiveness. But it does not provide any substantive evidence or logical reasoning to support the effectiveness or value of the product.

7. Black-or-White:

The Black-or-White fallacy, also known as false dichotomy or false dilemma, presents only two options or possibilities when, in reality, more exist. By oversimplifying a complex issue into a binary choice, this fallacy ignores shade and alternative perspectives. An example:

Politician: “You’re either with us or against us in the fight against crime. There’s no middle ground.”

This politician presents a false dichotomy by suggesting that there are only two options – supporting the fight against crime or opposing it. He does not acknowledge the possibility of alternative approaches or nuanced positions.

8. Bandwagon:

The Bandwagon fallacy argues that because something is popular or widely believed, it must be true or good. This fallacy appeals to the desire to conform to the majority opinion without critically evaluating the evidence or reasoning behind it. For instance:

Advertisement: “Join the millions of satisfied customers who have already switched to our product!”

This advertisement implies that the popularity of the product is a sufficient reason to switch to it. It does not provide any substantive evidence or reasoning to support its superiority over alternatives.

9. Hasty Generalization:

Hasty Generalization occurs when a conclusion is drawn from insufficient or biased evidence. This fallacy extrapolates from a limited sample size to make a broad generalization, overlooking variability and diversity within the population. An example:

Person A: “I met one rude person from that country, so everyone from that country must be rude.”

This statement makes a hasty generalization by inducing the behavior of one individual to an entire group. It does not consider factors that may influence behavior, such as cultural differences or personal characteristics.

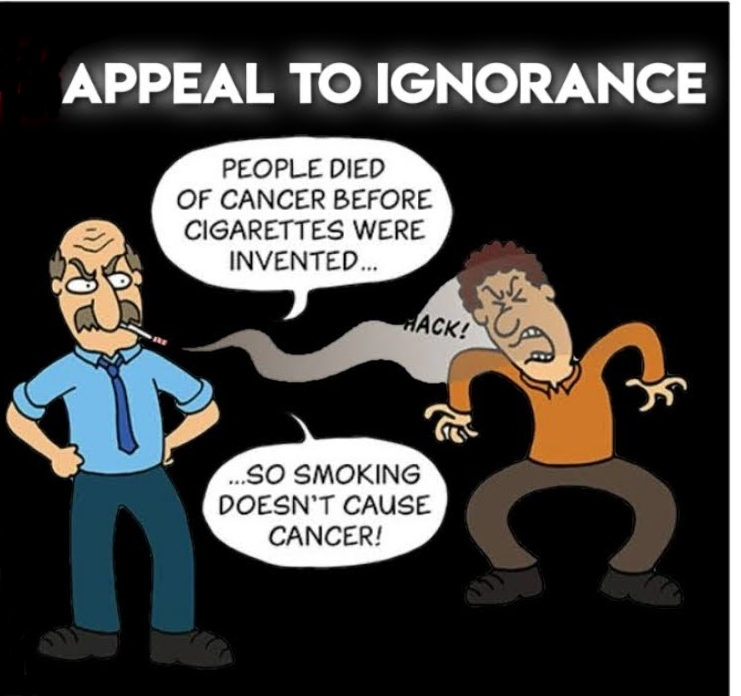

10. Appeal to Ignorance:

The Appeal to Ignorance fallacy asserts that a claim is true or false based on the absence of evidence to the contrary. It argues that because something has not been proven false (or true), it must be true (or false). However, absence of evidence is not evidence of absence. An example:

Person A: “Aliens must exist because there’s no evidence that they don’t.”

Person B: “Just because we haven’t found evidence of aliens doesn’t mean they necessarily exist. We need positive evidence to support the claim.”

In this exchange, Person A relies on the absence of evidence to support the existence of aliens, which is fallacious reasoning because lack of evidence does not necessarily prove the existence of something.

Conclusion

In conclusion, logical fallacies are common pitfalls in reasoning that can weaken arguments and lead to faulty conclusions. By familiarizing ourselves with these fallacies and learning to recognize them in both our own arguments and those of others, we can sharpen our critical thinking skills and engage in more rational and productive discourse. By striving for clarity, coherence, and logical rigor in our arguments, we can construct more compelling and persuasive cases while fostering constructive dialogue and understanding. Logical fallacies serve as cautionary reminders to approach arguments with skepticism, curiosity, and a commitment to truth-seeking, ultimately enhancing our ability to navigate the complexities of the world around us.